You know, having been working in the fitness industry since 1997, I’ve come across a ton of really braindead “interesting” articles in regards to women and training protocols. Whenever I’m reading an article that discusses program design, and brings up points in regards to the “science” behind a theory, I immediately stop reading, and scroll to the bottom of the page to see if I can find any reference articles or more importantly – research studies cited by the writer. I recently came across an article on the T-Nation website (www.T-Nation.com) by a writer named Jay Farrant titled “Women Shouldn’t Train Like Men”, and automatically, my interest was struck. I decided to begin reading this article with an open mind, because due to the title, I already had some reservations about wanting to engage in it at all. Being a woman who trains – and trains like a “man” I should add – I was hoping to actually find some research to support this writer’s extreme point of view. To my dismay, after scrolling to the bottom of the page, there was zero scientific theory presented to support the writer’s article. So, I wanted to take a moment to simply go over with a rebuttal of sorts with my own point of view about the subject and article itself.

First off, the original article can be found here: http://www.t-nation.com/training/women-shouldnt-train-like-men

The opening paragraph for this article spells out, and kind of touches briefly upon the major points the reader will encounter as they indulge in this parody of science:

Here’s what you need to know…

- Men generally don’t need to perform a lot of isolation work to get a great physique. Women need more isolation work, especially in the upper body.

- Regarding the bench press, women have to rely more on their triceps, shoulders, and back. That’s why the key to a good bench press for the female lifter is strong triceps and good mobility.

- For squats, females respond better to a mix of high volume and high intensity and don’t suffer with recovery issues as much as men.

- Women don’t often grind out reps like men do. They either get a heavy rep comfortably or just flat-out fail. This “shortcoming” allows females to train more frequently at high intensities and not worry about frying the CNS.

Now, after reading the article’s opening, I did find myself in agreeance with some of the bullet points brought up. In general, women do indeed have less upper body strength than men. So it is in fact important for women to look to train accessory muscles that can only help make big lifts like pull ups, push ups, and bench presses far easier to accomplish within pain/injury free ranges of motion over time. In the 3rd bullet point, I can agree with the writer to a certain extent. If the writer is referring to “intensity” by the scientific term defined as the amount of weight lifted during an exercise, meaning high intensity = heavy weight, then he is correct in that theory (1). There is enough research that has shown that High Volume training has a direct correlation to greater muscle hypertrophy (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8). But the part where the writer takes two great steps forward, and then crashes flat on his face for 3 steps back is in the final bullet point.

Women don’t often grind out reps like men do. They either get a heavy rep comfortably or just flat-out fail. This “shortcoming” allows females to train more frequently at high intensities and not worry about frying the CNS.

Ok, hold up there sir… What facts do you have to support this kind of statement? I know as MANY men as women who don’t “grind out reps”. This statement can be applied to both sexes, particularly the sect of the population not a part of the whole “hard-core training” crowd. Go to your average gym any day of the week, any hour of the day, and you’ll see men giving as much of a lackadaisical workout as the women who do nothing but lift 5 pound weights every visit. And often the men attempting to “grind out reps” in the gym are using poor form and performing exercises in a way that may lead to chronic injury. So really, was this kind of statement even necessary? And how about when a women DOES learn to enjoy training, and pushing the intensity as much as your harder working men do? Is it still a shortcoming then, and what exactly is she supposed to do to overcome this? Awesome, let’s lump women in a nice little box and undermine them at the same time. Great way of starting an article, but I digress, so let’s proceed shall we…

Female Physique Training

The writer goes on in this section to lay out his points regarding the best way to approach physique enhancement through exercises for women. Farrant seems to favor more isolation work for women than he does for men:

Men generally don’t need to perform a lot of isolation work to get a great physique. If you concentrate on getting strong by using the big lifts, men will generally get good results, but many women find it hard to press and pull heavy, and they often become arm dominant in those lifts.

That’s why I recommend more isolation work for women, especially for the upper body. For example, I’ll include two arm days per week. Because women have smaller muscles, they can isolate them more often and not worry about longer recovery periods.

I’m not sure if I agree with this statement. ANY person looking to enhance their physique, particularly for the stage, will need to do some form of isolation work whether male or female. And, this article is geared it seems towards the general gym goer as much as the physique competitor as the writer states the following:

Here are some general points regarding the areas of interest to most women:

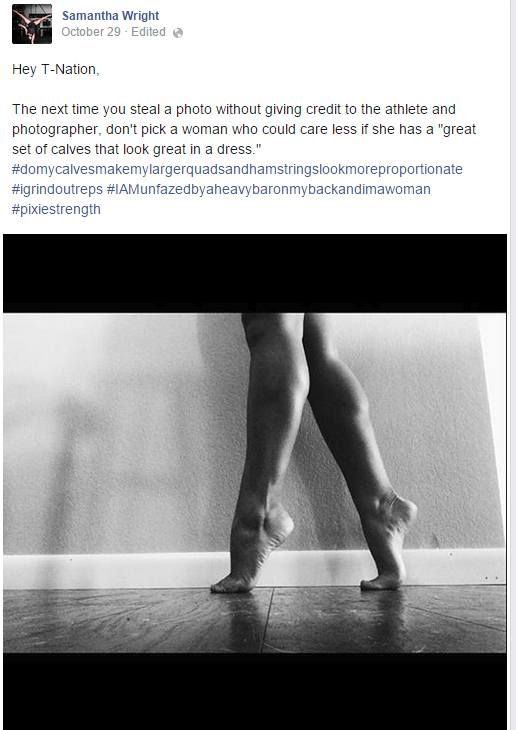

Calves Women should train calves 4 days a week in both vertical planes. Having a great set of calves on stage or in a dress looks great and will help make larger quads and hamstrings look more proportionate.

Compounds lifts however DO have a place for ALL trainees regardless to goals, and of course as long as injuries do not prevent them from being included. In life we tend to move the body as one unit, functionally, and on various planes of motion. For that reason alone, subjecting women to a mostly isolated program does nothing when it comes to not only creating a BALANCED physique, but a body that can move efficiently in the real world. To set a woman up on a program that takes away from this type of development based on a theory with NO scientific backing does a great disservice to women, and the fitness industry as a whole.

I wonder as well if the writer even considered that many women are weaker in big lifts because of the simple fact that they are not taught, nor encouraged, to perform them in the first place. Instead of shying women AWAY from these kind of lifts, why not simply teach proper form and motor patterns to successfully complete the lifts. And not only that, but allowing the trainee to use loads that she can comfortably control as she learns how to engage the proper muscles. All of our bodies, regardless to gender, develop and adapt along the lines of the SAME theory: the SAID Principle. This principle states:

Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demands (SAID) – (WIKIPEDIA)

SAID principle asserts that the human body adapts specifically to imposed demands. In other words, given stressors on the human system, whether biomechanical or neurological, there will be a Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demands (SAID).

So, what this means is that the HUMAN BODY will always adapt according to what it is given and asked to do over time. If you train for strength, you will get stronger. If you train for mass, you will get bigger. And if you train for speed, you’ll get faster. The list goes on and on. One of the major factors that can specifically influence how well or quickly one adapts are based within hormones, not training protocols specifically set for men and women. So what he’s saying isn’t entirely true, and leaves the reader with anecdote when it comes to how to properly design a training program for women, or how a female trainee should approach her own work in the gym.

Now, to play devil’s advocate, he does make a point which I can agree upon, increasing both volume and frequency of training a specific part or move during a cycle will lead to greater adaptation – and thus greater progress (whether hypertrophy or strength gains is your goal). But if this is what the writer meant, he should have been FAR more clear.

Programming for Women

The rest of the article is a hodgepodge of inconsistencies in regards to programming for women, based on the the writer’s recommendations.

As pointed out above, the writer clearly suggests that women stick to more isolated movements as the basis upon which their program design should be built, in particular for the upper body.

Different goals will determine different types of programs, of course, but for women who just want to look good, build strength, and stay healthy, something like the following would work great:

Day 1: Heavy Squat 1-2 x push/pull * – isolation work/fat-burning circuit

Day 2: Single Leg Exercise 1-2 x push/pull – isolation work/fat-burning circuit

Day 3: Heavy Deadlift 1-2 x push/pull – isolation work/fat-burning circuit

* Either 1-2 push movements and pull movements as single sets or 1-2 push/pull movements as a superset.

Examples of movements to do on heavy squat day include traditional squats, box squats, front box squats, wide stance squats, etc.

Examples of push movements include overhead presses, close-grip dips, and Arnold presses, while examples of pull movements include pulldowns, chin-ups, dumbbell upright rows, hang cleans, and high pulls.

Examples of exercises to do on heavy deadlift day include trap bar deadlifts, rack pulls, snatch-grip deadlifts, stiff-legged deadlifts, and traditional deadlifts.

Every single example given by Farrant is a COMPOUND MOVE. They are moves traditionally programmed for “men’s type workouts”. Isn’t this article about the very basis that women SHOULDN’T train like men? So this is where his entire theory starts to clearly fall apart. Farrant mentions, “isolation work/fat-burning circuit” as a part of heavy lifting days. However he gives no clear explanation as to what that means or entails.

He gives another example in a 4 or 5 day split routine, but the REAL kicker is in the final line of this protocol:

A 4 or 5 day weekly split could look something like this:

Day 1: Heavy Squat single leg hamstring/glute focused – isolation work

Day 2: Single Leg Quad Focused push/pull – isolation work

Day 3: Deadlift quad focused – isolation work

Day 4: Single Leg Hamstring/Glute Focused push/pull – isolation work

Day 5: Sprint/Track Work strongwoman (flipping tires, battle ropes, sled drags, sled pushes) – isolation work for lagging body parts – sport – walk – mobility work

The key points in every training session are to train lower body and finish off with some type of isolation circuit or exercise. The quads, hamstrings, and glutes get trained frequently but still get trained at different intensities and movement patterns throughout the week.

The writer consistently insists that women train the lower body EVERYDAY or at least every training session. He gives no support nor reasoning as to WHY this should be followed except his theory that women recover better than men, and don’t train at high enough intensities to “fry” the CNS. And even though he attempts to move between hip and glute dominant work, the main concern is that overtraining and overreaching can still occur with this kind of set up. It is in RECOVERY that the body has a chance to adapt, grow and change. So training any single body part or group consecutively for any period of time can still affect the CNS. Training a body part daily isn’t necessarily the best way to go about true progress and change in the long term as too much high intensity work done repeatedly can lead to overtraining, as research has clearly shown (9, 10).

In the writer’s attempt to solidify a protocol, he simply skims along the outskirts of providing any kind of clear direction or fact. What this does for the reader as a whole is just lead to confusion.I’m personally scratching my head trying to fill in the blanks where Farrant left off, offering nothing but generalizations and unclear suggestions about how I, or any woman should consider training for overall development.

Female Strength – The Big 3 Lifts

The final part of this article is where I feel Farrant shines in his expertise. Farrant is a powerlifter (www.JayFarrant.com) and a strength and conditioning coach who surprisingly trains a number of women. Going off of what he shares on his site, he seems like a pretty knowledgeable guy. But it is in this section where the article takes a right angle turn to the left, and disjoints itself from the earlier topic.

Farrant brings ups, and fully discusses (intelligently) some great points on the 3 major lifts as they relate to women:

- The Squat

- The Bench Press

- The Deadlift

These three sections were excellent, but they are not connected to the content above entirely. His earlier points seem to allude more to physique development and training for aesthetics. The later writing, shifts more towards powerlifting and maximal strength focused athletes. In fact he goes on to say how he recommends raw female lifters in training protocols. This isn’t a problem, particularly when the article is about women training like men – and why we shouldn’t. However, when you start the article focusing on physique development, and then you make a complete 180 to talk about strength work without any kind of lead in and separation between the two approaches, it makes the entire article seem unplanned, disorganized, and therefore further unreliable.

What I find incredibly interesting is that this strength and conditioning coach, who works with tons of women, would even write an article with such a generalized, and somewhat demoralizing, approach. There could have been a more tactful way for him to approach this topic that could get the point across without completely undermining and offending an entire gender, and in particular, those of us who prefer to train just as hard (if not harder) than the boys.

But I think the icing on the cake was the response from the woman featured in the article’s photo. Samantha Wright who is indeed a powerhouse in her own right. She’s a Team USA athlete and 2016 Olympic contender for Weight Lifting. The girl is no joke, and is internationally recognized for her athletic accomplishments. Samantha couldn’t have put it any better:

- Marx, J.O., Ratamess, N.A., Nindl, B.C., Gotshalk, L.A., Volek, J.S., Dohi, K., Bush, J.A., Gomez, A.L., Mazzetti, S.A., Fleck, S.J., Hakkinen, K., Newton, R.U., and Kraemer, W.J. (2001, April) Low-volume circuit versus high-volume periodized resistance training in women. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 33(4), 635-43.

- Schoenfeld BJ, Ratamess NA, Peterson MD, Contreras B, Sonmez GT, Alvar BA. Effects of different volume-equated resistance training loading strategies on muscular adaptations in well-trained men. J Strength Cond Res. 2014 Oct;28(10):2909-18. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000480. PubMed PMID: 24714538.

- Berger, R. A. Effect of varied weight training programs on strength. Res. Q. 33:168–181, 1962.

- Burd, N.A., West, D.W., Staples, A.W., Atherton, P.J., Baker, J.M., Moore, D.R., Holwerda, A.M., Parise, G., Rennie, M.J. and Baker, S.K., 2010. Low-load high volume resistance exercise stimulates muscle protein synthesis more than high-load low volume resistance exercise in young men. PloS One, vol. 5, no. 8, pp. e12033.

- Burd, N.A., Holwerda, A.M., Selby, K.C., West, D.W., Staples, A.W., Cain, N.E., Cashaback, J.G., Potvin, J.R., Baker, S.K. and Phillips, S.M., 2010. Resistance exercise volume affects myofibrillar protein synthesis and anabolic signalling molecule phosphorylation in young men. The Journal of Physiology, 20100625, Aug 15, vol. 588, no. Pt 16, pp. 3119-3130 ISSN 1469-7793; 0022-3751. DOI 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.192856 [doi].

- Tan, B., 1999. Manipulating resistance training program variables to optimize maximum strength in men: a review. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 289-304.

- Schoenfled, B.J., 2010. The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research / National Strength & Conditioning Association, Oct, vol. 24, no. 10, pp. 2857-2872 ISSN 1533-4287; 1064-8011. DOI 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e840f3 [doi].

- Kraemer, W.J. and Ratamess, N.A., 2004. Fundamentals of resistance training: progression and exercise prescription. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 674-688.

- Fry RW, Morton AR, Keast D. Overtraining in athletes. An update. Sports Med. 1991 Jul;12(1):32-65. Review. PubMed PMID: 1925188.

- Kreher JB, Schwartz JB. Overtraining syndrome: a practical guide. Sports Health. 2012;4:128–138.